Elmore Leonard's 11th Rule of Writing

I’ve always enjoyed Elmore Leonard’s novels and seen him as one of the true stylists of popular fiction. In a review, I even described my pal Christopher G. Moore as the “Elmore Leonard of Bangkok” and I meant it as a compliment. But I have a bone to pick with the great Elmore.

I just read a book of Elmore’s short stories from 2004 titled “When the Women Come Out to Dance.” In many ways it’s superb. The title story turns on the particularly American kind of hardness and determination that takes a character who is not bad into a situation that leaves them ineradicably among bad people.

So what’s the problem? Movie stars, that's what.

In one of the early stories in the book, a character is described as being a “Jill St. John type.” I looked her up. She doesn’t appear to have had a major movie role for about 28 years before Elmore wrote the story, but I suppose her bikini-clad appearance in an ancient Bond film made an impression on him.

In two – not one, but two – of the later stories in the book, there’s a character who’s described as looking like (or smiling like) Jack Nicholson.

This isn’t the work of a great stylist. This is on the level of Dan Brown. (Remember that in The Da Vinci Code, Brown’s hero, the dumbest professor Harvard ever employed, is described thus: “He looked like Harrison Ford.” I wonder if, after the movie came out, later editions updated that to “…He looked like Tom Hanks.”)

This would be a cheap technique if a journalist used it. For a writer with the descriptive powers of Elmore, it’s a real shame.

In his famous 10 Rules of Writing, Elmore says: “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.” That’s probably why he didn’t write “He looked like Jack Nicholson in ‘The Shining’ in the scene where he’s coming through the door with the axe and shouting ‘Here’s Johnny’ with a demented enjoyment on his face.” Too much detail.

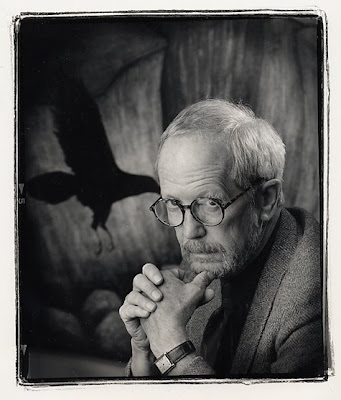

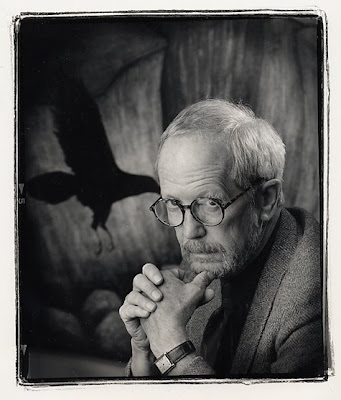

Well, if you were trying to describe Elmore, how would you do it? Here’s his picture. I could describe him as “looking like Roger Whittaker.” Mean anything to you? Perhaps you don’t recall much about British easy-listening music of the 1970s. If you did, you’d have a picture. But why should you?

That’s exactly why I don’t like to see Elmore describe a character as looking like a particular movie star.

That doesn’t mean Elmore’s style should be discounted. (Read his 10 rules below. They’re very good in a folksy American sort of way.) But let’s first add an 11th rule: Don’t describe characters as looking like a particular movie star.

Elmore Leonard's Ten Rules of Writing

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

1. Never open a book with weather. If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

2. Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s “Sweet Thursday,” but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . .

. . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.”

5. Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories “Close Range.”

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

And finally:

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

My most important rule is one that sums up the 10.

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing. (Joseph Conrad said something about words getting in the way of what you want to say.)

If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character—the one whose view best brings the scene to life—I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.

What Steinbeck did in “Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. “Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, “Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled “Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter “Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: “Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.”

“Sweet Thursday” came out in 1954, when I was just beginning to be published, and I’ve never forgotten that prologue.

Did I read the hooptedoodle chapters? Every word.

I just read a book of Elmore’s short stories from 2004 titled “When the Women Come Out to Dance.” In many ways it’s superb. The title story turns on the particularly American kind of hardness and determination that takes a character who is not bad into a situation that leaves them ineradicably among bad people.

So what’s the problem? Movie stars, that's what.

In one of the early stories in the book, a character is described as being a “Jill St. John type.” I looked her up. She doesn’t appear to have had a major movie role for about 28 years before Elmore wrote the story, but I suppose her bikini-clad appearance in an ancient Bond film made an impression on him.

In two – not one, but two – of the later stories in the book, there’s a character who’s described as looking like (or smiling like) Jack Nicholson.

This isn’t the work of a great stylist. This is on the level of Dan Brown. (Remember that in The Da Vinci Code, Brown’s hero, the dumbest professor Harvard ever employed, is described thus: “He looked like Harrison Ford.” I wonder if, after the movie came out, later editions updated that to “…He looked like Tom Hanks.”)

This would be a cheap technique if a journalist used it. For a writer with the descriptive powers of Elmore, it’s a real shame.

In his famous 10 Rules of Writing, Elmore says: “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.” That’s probably why he didn’t write “He looked like Jack Nicholson in ‘The Shining’ in the scene where he’s coming through the door with the axe and shouting ‘Here’s Johnny’ with a demented enjoyment on his face.” Too much detail.

Well, if you were trying to describe Elmore, how would you do it? Here’s his picture. I could describe him as “looking like Roger Whittaker.” Mean anything to you? Perhaps you don’t recall much about British easy-listening music of the 1970s. If you did, you’d have a picture. But why should you?

That’s exactly why I don’t like to see Elmore describe a character as looking like a particular movie star.

That doesn’t mean Elmore’s style should be discounted. (Read his 10 rules below. They’re very good in a folksy American sort of way.) But let’s first add an 11th rule: Don’t describe characters as looking like a particular movie star.

Elmore Leonard's Ten Rules of Writing

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

1. Never open a book with weather. If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

2. Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s “Sweet Thursday,” but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . .

. . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.”

5. Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories “Close Range.”

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

And finally:

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

My most important rule is one that sums up the 10.

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing. (Joseph Conrad said something about words getting in the way of what you want to say.)

If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character—the one whose view best brings the scene to life—I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.

What Steinbeck did in “Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. “Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, “Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled “Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter “Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: “Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.”

“Sweet Thursday” came out in 1954, when I was just beginning to be published, and I’ve never forgotten that prologue.

Did I read the hooptedoodle chapters? Every word.

Comment

-

Comment by Jack Getze on July 16, 2009 at 7:51am

-

Be Cool and Get Shorty both start with the character, Chili Palmer, telling you what's up. Third person POV. You won't find the author in either one of those books.

-

Comment by John McFetridge on July 16, 2009 at 5:05am

-

Yeah, I'm a big fan of Raymond Carver. I'm going through a whole short story binge these days.

-

Comment by I. J. Parker on July 16, 2009 at 4:46am

-

I absolutely follow the Lourdes example. It's clearly a character's pov. But I'm not at all sure about the "They" beginnings. That may well be the author as narrator -- unless a later passage introduces the observer as someone other than the author.

-

Comment by John Dishon on July 16, 2009 at 3:56am

-

*"being" should be "began" above.

-

Comment by John Dishon on July 16, 2009 at 3:46am

-

I see your "Hanging Out at the Buena Vista" and raise you "A Small, Good Thing".

-

Comment by John Dishon on July 16, 2009 at 3:35am

-

Get Shorty and Be Cool both open up with a narrator. Be Cool even starts with "They", as if the narrator is on the other side of the street pointing at the characters.

The Jill St. John part is also narrated. Here is the paragraph with that description:

Mrs. Manhood, with her wealth, her beauty products, looked no more thirty. Her red hair was short and reminded Lourdes of the actress who used to be on TV at home, Jill St. John, with the same pale skin.

Unless Lourdes, is referring to herself in third person, that's a narrator. Also, I noticed he being 4 of those 9 stories with "They".

-

Comment by Jack Getze on July 16, 2009 at 2:38am

-

I have to go back and look now, but I was under the same impression as John -- i.e., that Elmore never narrates as an author. It's his biggest, guiding rule -- an invisible author.

The other thing John's right about -- I have to shut up about Elmore until August.

-

Comment by John McFetridge on July 16, 2009 at 1:55am

-

There is no narrator in Elmore Leonard novels - everything is from a character's pov. It's one of the things you can see develop over his books, his refining of that removal of the narrator. Cool stuff.

-

Comment by Matt Rees on July 16, 2009 at 1:45am

-

Jack, that'd be fine. But in these stories, the descriptions of characters as looking like a particular movie star are by the narrator. That's quite different.

-

Comment by B.R.Stateham on July 16, 2009 at 1:25am

-

Rules, my friend, are made for two things: One; they're made to give a set of broad-spectrum guidelines. They're like a GPS system of navigation for a writer. They point you in a certain direction.

Two; rules are made to be broken. If you religiously follow rules you fail to develop a writing style you can call your own. So everyone, sooner or later, breaks rules here and there.

Welcome to

CrimeSpace

CrimeSpace Google Search

© 2025 Created by Daniel Hatadi.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of CrimeSpace to add comments!