Scene of the Crime, new post: Chicago in the Blood

Chicago in the Blood

February 26, 2010 by Scene of the Crime

“An understated crime fiction gem . . . a wildly thought-provoking whodunit,” is how the Chicago Tribune termed Barbara Fister’s first Chicago-based crime novel featuring ex-cop and current PI Anni Koskinen. That work, In the Wind, finds Anni herself the object of an FBI investigation when she unwittingly helps a fugitive escape.

“An understated crime fiction gem . . . a wildly thought-provoking whodunit,” is how the Chicago Tribune termed Barbara Fister’s first Chicago-based crime novel featuring ex-cop and current PI Anni Koskinen. That work, In the Wind, finds Anni herself the object of an FBI investigation when she unwittingly helps a fugitive escape.

Fister locates her work in Chicago and takes the challenge of writing that oft-used locale seriously, as evidenced by a Publishers Weekly contributor who wrote of In the Wind: “The Windy City already has plenty of fictional PIs, but they’ll have to make room for the gutsy and appealing Anni Koskinen.”

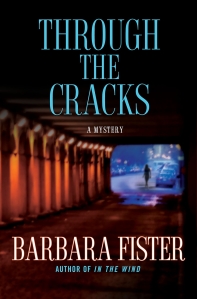

Fister, dubbed the “heir apparent to Sara Paretsky,” followed up this successful first Anni Koskinen mystery with a second, Through the Cracks, out this May. Here the indefatigable PI takes on a serial rapist in a story that Publishers Weekly called a “gritty mystery [that is] well above the norm.” The same

reviewer thought that Anni Koskinen’s “empathy with both cops and

victims as well as her fierce, brittle independence make her easy to

root for.”

Barbara, thanks for taking the time to drop by Scene of the Crime and sharing some thought on location in your fiction.

First, describe your connection to Chicago. How did you come to live there or become interested in it? And, if you do not live on site,

do you make frequent trips there?

Chicago was the big city when I was growing up two hours north in Wisconsin. My parents would take us there to see tall

buildings and visit museums and look at the lights and shop windows on

the Miracle Mile at Christmastime. It wasn’t until much later that I

got to know the real Chicago, the city of nearly 200 neighborhoods, a

city that had built a network of beautiful parks and reversed the flow

of the Chicago River in a spirited engineering feat—and has block after

block on the South and West Sides that look as if they’d been through a

war and haven’t been rebuilt. That’s the mixed-up, complicated city I

came to love. I spent part of a sabbatical there, visit often, and my

son has obligingly moved to the area so now I even have a couch to

sleep on.

What things about Chicago make it unique and a good physical setting in your books?

your books?

Though every neighborhood in the city is different, Chicago in aggregate is the quintessential American city: broad-shouldered,

earnest, diverse, troubled. It is divided by race and class and has

always been buffeted and strengthened by waves of immigration. It now

has the second-largest Mexican American population in the US after L.A.

It’s deeply corrupt and has a history of bad race relations, form the

deadly 1919 riots to the mayor’s “shoot to kill” order given during the

riots of 1968, and the virulent hostility of the city council when the

great Harold Washington was elected its first black mayor. But for all

that, it is home to the friendliest people in the world, or at least

that’s been my experience. I suspect some southern hospitality came

packed in the bottom of footlockers during the Great Migration. In Through the Cracks, my narrator Anni Koskinen visits an acquaintance in East Garfield Park, a poor black neighborhood on the West Side.

“There weren’t many businesses in this part of town, at least the kind that were on the tax rolls, but the

streets were always humming with activity. On this early evening, a

cluster of men were gathered around a car with its hood up while a

group of boys hung out nearby, laughing and exchanging rabbit punches.

An ancient man with a porkpie hat squashed on his head was limping from

one person to another asking if anyone could spare some change for the

bus. As I parked and climbed out of my car, a man relaxing on his front

stoop with a can of malt liquor and a cigarette nodded at me. ‘How you

doing today?’ he asked politely.

“An average day in the 11th district would see a dozen arrests for battery, theft, prostitution, and narcotics. It

was a dangerous neighborhood, and most of the residents had difficult,

hardscrabble lives. But in spite of all that, people had small town

manners and were more likely than in North Side neighborhoods to smile

at strangers and say hello.”

That has been my experience in Chicago. Life’s not always easy and the climate can be frigid, but the people are warm.

Did you consciously set out to use Chicago as a “character” in your books, or did this grow naturally out of the initial story or

stories?

Setting is important to me as a reader, both as the petri dish for a story and as an influence on the characters. Anni Koskinen,

my narrator, would be a different person if she lived somewhere else.

I’m not sure the Chicago setting has the status of “character” exactly,

but you can’t take the D.C. out of George Pelecanos or the New York out

of Lawrence Block. A long time ago Linton Weeks wrote an essay in the Washington Post complaining

about the “no style style” used in popular thrillers, language that had

no flavor and was interchangeable among authors. I think some books

have a “no setting setting” but I don’t enjoy spending time there.

How do you incorporate location in your fiction? Do you pay overt attention

How do you incorporate location in your fiction? Do you pay overt attention

to it in certain scenes, or is it a background inspiration for you?

I think I must have some kind of mental GPS implanted in my brain; I never think up a scene without deciding where it is happening.

Because Chicago’s neighborhoods are stamped so distinctively by

ethnicity and income, the precise latitude and longitude where

something happens make all the difference.

How does Anni Koskinen interact with her surroundings? Is she a native, a blow-in, a reluctant or enthusiastic

inhabitant, cynical about it, a booster? And conversely, how does the

setting affect your protagonist?

Anni Koskinen lives in Humboldt Park, a neighborhood that is at a crossroads in many senses of the word. It’s home to Chicago’s

Puerto Rican community, and there are lots of visible signs of Puerto

Rican pride as well as great coffee and guava pastries. It also has

many black and Mexican American residents, which makes for some

complicated boundary disputes when it comes to gang turf. It’s next

door to Ukrainian Village, which still has several Russian Orthodox and

Ukrainian Catholic churches with gleaming onion domes. It’s also ripe

for gentrification, so the turf warfare isn’t just among gangs. Anni

grew up in Chicago and, for a time, on the North Shore. She’s mixed

race and is used to traveling without a passport between classes and

races, which means she feels at home anywhere in the city, but not

necessarily as if she belongs anywhere in particular. For reasons of

geography, she’s more Cubs inclined than Sox, but she’s ecumenical

enough to be happy when the Sox win the pennant.

Has there been any local reaction to your works?

In the Wind got a generous review from Paul Goat Allen in the Chicago Tribune and Sean Chercover, who lives there and writes about the city, seems to

think I got the setting right. Otherwise, I haven’t heard much one way

or the other.

Of the novels you have written set in Chicago, do you have a favorite book or scene that focuses on the place? Could you quote a

short passage or give an example of how the location figures in your

novels?

Across the street from Daley Plaza there’s a landmark building that is typical of Chicago’s contradictions. The oldest

congregation in the city’s history, the United Methodist Church began

construction on their current home in the 1920s, building a monument to

church and commerce that would incorporate a place of worship, office

space and a tiny chapel high above the city. Though this prime real

estate still leases offices, homeless people are welcome to spend time

in the sanctuary, seeking warmth in the winter or cooling off on hot

summer days. Every May an ecumenical service is held there for the

indigent poor buried by the county at Homewood Cemetery south of the

city. Anni describes it:

“It was an annual memorial service, held at the Chicago Temple, that strange neo-Gothic skyscraper in the Loop that combines Methodist

ministry and fifteen floors of office space. A few dozen people would

gather there at the end of May to remember those buried by the county

at public expense. Not that much was expended—embalming performed by

students of mortuary science who needed the practice, a forty-dollar

pine box, and a few square feet of a trench in the Homewood cemetery,

where they were interred, a dozen at a time, as soon as investigators

in the morgue detail were certain no one else would foot the bill.

Fifteen or twenty of the three hundred or so buried by the county each

year didn’t even have a name. My mother was buried there, identified

only by a number until Jim Tilquist helped me track her down. I had

only the vaguest memories of her, and never found out how she died, but

I went to the service every spring, and sometimes took the trip with

her to Homewood in my dreams.”

In Through the Cracks, Anni tries to warn a girl whose sister is  missing that the search may not turn out well, and she thinks about her mother and visiting the cemetery for the first time.

missing that the search may not turn out well, and she thinks about her mother and visiting the cemetery for the first time.

“I stared out at the street, thinking about the few memories I had of her: a warm lap, an Indian block-print skirt with a mysterious spicy

scent. A string of blue glass beads that I rolled between my fingers

and held up to the light to see their clear, sapphire glow.

“Much clearer was the memory of the day Jim drove me to the cemetery in a suburb south of the city where we’d learned my mother had been

interred with other indigents in an unmarked grave. I’d bought a bunch

of flowers with my own money. When we drove through the cemetery gate,

my heart lifted to see such a beautiful place, shady and green. Jim

asked for a map at the front office and we drove to the area at the far

end of the cemetery that was labeled ‘Garden of Peace.’ But when we got

there, it wasn’t a garden at all. Weeds grew up through disturbed

earth; rocks and dirt lay in piles. I got out and walked across the

uneven ground, a bitter wind blowing hair in my face as a backhoe

carved a trench near the back fence. I remembered feeling Jim’s hand on

my shoulder, hearing him ask if I was ready to go home, shaking my head

helplessly. I didn’t know where to leave the flowers.”

The site where Cook County buries its poor is a measure of the poverty and neglect that is so common in Chicago; the service at

the Temple is a recognition that at least some feel those buried there

should not be forgotten.

Who are your favorite writers, and do you feel that other writers influenced you in your use of the spirit of place in your

novels?

Since setting is so important to me, I’m sure every writer I love has helped me think about how place influences the reading

experience. And there are so many. I love the work of George Pelecanos,

Denise Mina, Sean Doolittle, Reggie Nadelson, and Richard Price, all

masters of setting. I’m fascinated by the Scandinavian writers who

write so realistically about the impact of crime and the things we’re

all capable of: Arnaldur Indridason, Karin Fossum, Jo Nesbo, and Johan

Theorin, among others. I also love books by Sam Reaves and Sean

Chercover (who really get Chicago), Ed Dee (who gets New York), Martin

Cruz Smith (who gets Russia), John McFetridge (who owns Toronto), Deon

Meyer (who speaks fluent South African in more than one language),

Timothy Hallinan and John Burdett (who make Bangkok so real), Adrian

Hyland and Peter Temple (whose Strine is so expressive), David Corbett

(who won’t let us forget what we did to El Salvador and what we keep

doing to our immigrants). Of the old school there’s Elmore Leonard,

Ed McBain, the late Robert B. Parker, Sjowall and Wahloo … I could go

on and on. Some people think book publishing is broken, but one thing

for sure: storytelling isn’t. I will never run out of great things to

read or places to visit.

Barbara, thanks for a fascinating discussion and for bringing Chicago to life for us.

Welcome to

CrimeSpace

CrimeSpace Google Search

© 2024 Created by Daniel Hatadi.

Powered by

![]()

You need to be a member of CrimeSpace to add comments!